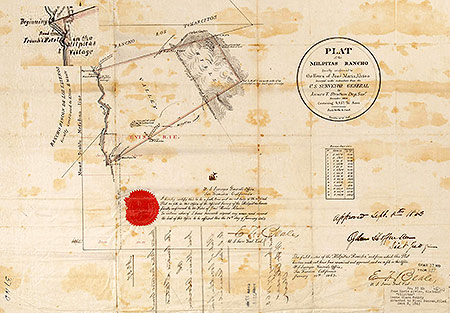

Although early maps consistently identify the tract of land as Rancho Milpitas or Milpitas Rancho, José Alviso also named this property Rancho San Miguel, in my opinion in honor of his grandparents who were born and married in San Miguel de Horcasitas, Sonora, New Spain before their migration to Alta California in 1776. This “alternate” name appears on several deeds to various individuals, including one dated February 14th, 1856 for a northwestern portion of land sold to Milpitas township pioneer Michael Hughes.

According to the history described in the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form filed in 1997 by the City of Milpitas, the original Alviso Adobe was built in 1837 as a single-story Spanish-style adobe. It is worth noting that by then, the Alviso family was comprised of José, his wife Juana Francisca Galindo, as well as six children ranging in age from 12 years to 2 years. This raises a substantive question in my mind: Was the family residing in another location before 1837, such as in El Pueblo de San José de Guadalupe, where José had been Alcaldé the year before, or, instead, was the Alviso Adobe actually built earlier than 1837?

A major clue is contained in José’s second petition dated November 1st, 1834 to the Town Council of Pueblo de San José asking again for a grant of the tract of land that eventually became Rancho Milpitas. In it in part he declares (in the following translation from the original Spanish), “I herewith present for the purpose of asking for the concession of the said tract of land in ownership within the limits described on the map, in consideration of the stock (author’s note: his earlier herd of 200 cattle by then had grown into a herd of 600 cattle and 30 mares) I possess as set forth and the improvements I have on said place, consisting of two walled houses, an orchard of sixty fruit trees, and a vineyard of six hundred vines, and other lands enclosed and cultivated.” Such extensive “improvements” were offered frequently as proof that the prospective grantee was acting to utilize the land productively as an upstanding member of the community and not let the land be idle as a personal instrument of land speculation. Given this fairly detailed documentation, I ask, were either of these “two walled houses” actually the same one (albeit upgraded years later to two stories) that currently exists? If yes, which I believe is certainly possible and even likely, then today’s adobe actually was built in 1834 or earlier and not in 1837 or later.

As José’s children grew up to raise their own families, several additional adobes were built to the south along Piedmont Road, but they were demolished in the early 1900s after those Alviso descendants no longer owned these partitions of land.

Originally Rancho Milpitas had been part of the outlying area of El Pueblo de San José de Guadalupe. Indeed, proof of this is that almost all of José’s grant applications for “the tract of land named Milpitas” had been carefully reviewed and recommended to the Governor by the Ayuntamiento (i.e., Town Council) of the Pueblo. The time-consuming procedure even required the testimony of three upstanding citizens to certify his worthiness as a member of the community.

(Page Two—click here)